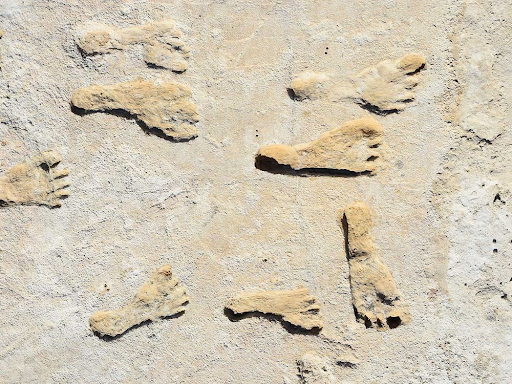

In a new update regarding footprints found in White Sands National Park, New Mexico in September 2021, it has been determined that the humans were on the North American continent thousands of years before what was previously thought.

In 2021, the US Geological Survey researchers and scientists drew the conclusion that the ancient human footprints discovered in New Mexico were between 21,000 and 23,000 years old. This discovery dispelled previous records, and pushed the known date of human presence in North America back by thousands of years, implying that early inhabitants co-existed with megafauna, many of which are now extinct due to the Pleistocene extinction event.

In a follow-up study published in Science on October 5, 2023, researchers analyzed the date of the footprints using two new independent approaches. The results confirmed what many scientists suspected; the footprints date back to the same age range as the original estimate.

While the results were truly remarkable, the 2021 results began a global conversation among the scientific community regarding the accuracy of scientific dating of the ages.

“The immediate reaction in some circles of the archeological community was that the accuracy of our dating was insufficient to make the extraordinary claim that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. But our targeted methodology in this current research really paid off,” said Jeff Pigati, USGS research geologist and co-lead author of a newly published study that confirms the age of the White Sands footprints.

The argument was centered on the accuracy of the original ages found in 2021, as they were obtained by radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon dating is a method for determining the age of an object containing a radioactive isotope of carbon. The age of the White Sands footprints was initially determined by comparing the sample to the common aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosa. However, these aquatic plants acquire carbon from dissolved carbon atoms in the water rather than air, which many scientists argue could potentially cause the measured ages to be too old.

“Even as the original work was being published, we were forging ahead to test our results with multiple lines of evidence,” said Kathleen Springer, USGS research geologist and co-lead author on the current Science paper. “We were confident in our original ages, as well as the strong geologic, hydrologic, and stratigraphic evidence, but we knew that independent chronologic control was critical.”

For their follow-up study done this year, researchers focused on radiocarbon dating of conifer pollen rather than Ruppia cirrhosa because it comes from plants on land. This eliminated issues that arose with the aquatic plants used during the initial dating of the footprints. The researchers used approximately 75,000 pollen grains for each sample they dated, picking them from the same layer that the samples of Ruppia cirrhosa were found in to ensure consistency.

In addition to the radiocarbon dating with pollen samples, the research team also used a type of dating method called optically stimulated luminescence. This is a technique used to date fossils in sediments through ionized radiation to determine the last time a mineral was exposed to sunlight. Using this method, they found that quartz samples collected within the layers that the footprints came from had a minimum age of 21,500 years, providing further support to the radiocarbon results.

With 3 separate studies providing evidence supporting the same approximate age, scientists concluded that it was highly unlikely that they were all incorrect, and settled on the 21,000 to 23,000 year age range for the White Sands footprints.